Holger Nehring

History and Politics

And twelve points go to…Sandie Shaw from the United Kingdom for her hit ‘Puppet on a String’. Nothing could have been further from the world of those who protested on Western Europe’s streets in 1967 than the unpolitical lyrics and mainstream sound of that year’s winner of the Eurovision Song Contest in Vienna.

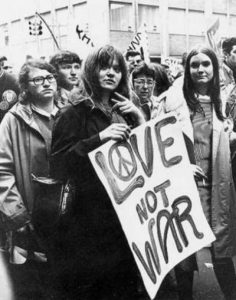

The protesters did not want to be puppets on a string. They longed to break free: from hierarchies, from established norms, from mainstream politics, from the Cold War.

Many have used ‘1968’ as shorthand for the massive protests that engulfed Europe and the world around that time. But for many countries in continental Europe, 1967 was the year when it was all happening.

1967 was the year when utopias of freedom, socialism and peace clashed with the cruelty of the US war in Vietnam and the politics of the Cold War in Europe.

2 June 1967: the West German Benno Ohnesorg was shot dead by an undercover police officer at a demonstration against the Vietnam War in Berlin. This was the date when street battles and political violence seemed to have returned to German politics.

For the protesters, the trigger-happy police officer Karl-Heinz Kurras, who had shot Ohnesorg, was the embodiment of the quasi-fascist West German state: intolerant of democratic protesters, full with former Nazis as civil servants and government ministers, and obsessed with fighting communism rather than protecting the freedom of speech. The killing led to a massive surge in their demonstrations.

Protesters regarded themselves as an extra-parliamentary opposition that protected democracy. The German parliament was discussing a new Emergency Law at the time, which was supposed to provide more powers for the government, the police and army under exceptional circumstances.

The brutality of the US war in Vietnam appeared to them to be part of the same logic that had led to Ohnesorg’s killing: it was where the Cold War had become hot and where the USA, West Germany’s main Cold War ally, seemed to reveal its true face. This was not the American dream, but the brutality of war and the US military.

Protests also took place in France, although they still remained centred primarily on university campuses in Paris and the provinces. They focused on the quality of student accommodation and full classrooms. And they bemoaned the lack of effective political representations for students in University committees.

Protests began to unfold in Italy in 1967 as well. They started at the private Catholic universities in Trento and Milan and then spread around the country. In November 1967, students occupied a building at the University of Turin. Demonstrations around Italy culminated at the end of this year in a pilgrimage from Milan to Rome, which was led by the socialist pacifist Danilo Dolci.

A key influence on Italian protesters was Catholic liberation theology: it had come to Italy from Latin America and emphasised the social responsibility of Catholic Christianity, portraying Jesus as the first revolutionary.

1967 was the year when separate protests, in different cities and countries, first came to be seen as part of one ‘transnational moment of change’, as the historians Rainer Horn and Padraic Kenney have called it. This moment was only possible because of the power of the mass media, and television in particular: they made separate protests appear as part of a larger movement.

Today many see the protests as part of a generational revolt: younger students rose up against the complacency of their parents’ generation. But this interpretation is problematic: many protesters were not students or not particularly young, and many protesters rejected the generational interpretation as one that explained away their political commitment by referring to their immaturity.

True, the protests were directly related to the significant expansion of higher education across Western Europe from the early 1960s, and the consequences this expansion had for the quality of student accommodation as well as for the representation of students on university committees.

But more was required to make the protests to relevant to so many students. Fundamentally, the protests were about the nature of democracy and politics.

The memory of National Socialism and fascism gave the protests their particular political power. The protesters called their governments fascists. By contrast, the mass media and their opponents evoked the spectre of the breakdown of democracy in the 1920s and 1930s, where violent street battles had replaced parliamentary debates.

The protests thus signalled the end of the political order that had emerged in Western Europe after the Second World War: focused on representative democracy through parliaments and elections – and dependent on organisations, such as parties and trade unions, to filter these views. The protesters, by contrast, argued for democracy from below – for direct democracy.

In the end, that political order remained in place.

There still is something remarkable about the protests: the way in which politics merged with culture. The protests gave expression to what historians have called a ‘cultural revolution’: a monumental change in lifestyles, music and, more broadly, assumptions about how society and politics should work.

Instead of hierarchy and order, this cultural revolution emphasised flexibility and joy; it left the memory of the war behind and was instead optimistic about the future. What had been black and white became technicolor. Self expression replaced conformity. It was embodied in the many communes that emerged in some West European cities, such as West Berlin and Frankfurt.

On the one hand, this cultural revolution fuelled the growth of individualism and consumerism. Many former student leaders in France ended up as executives of major French corporations. They now became advocates for neo-liberal economic policies – the constant was their emphasis on individualism, self-fulfillment and their rejection of the state.

On the other hand, the emphasis on individual rights and freedom were the preconditions to the feminist and gay and lesbian rights movements that emerged across Europe over the course of the 1970s. They embodied new forms of community, communal living and social activism. The personal had become political.

Be First to Comment